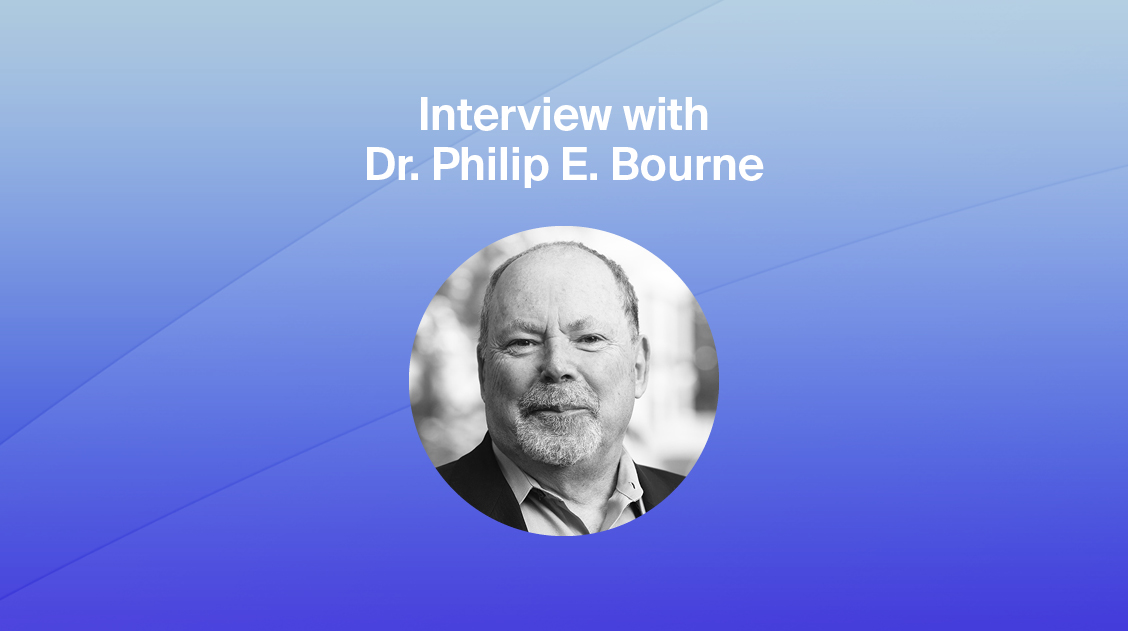

Interview with Dr. Philip E. Bourne, Data Science Honoree

, IBiomolecules has an exciting new biomolecular data science Special Issue in honor of Dr. Philip E. Bourne, a distinguished scholar in the field. In this article, we ask Phil about his career and what he sees for the future of the field.

Phil, as he is known to all—from students to university presidents and beyond—is the founding Dean of the School of Data Science (SDS) at the University of Virginia (UVA).

Prior to that, Phil was the first Associate Director for Data Science at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), where he led a novel Big Data to Knowledge initiative.

Before this, at the University of California San Diego, Phil was a Professor of Pharmacology, and then Associate Vice Chancellor.

The Special Issue shows how Phil’s contributions to multiple, disparate fields have coalesced into a new field of biomolecular data science.

This tribute to Phil intentionally intertwines the personal and the professional—as one can gather from even just brief interactions with him, Phil-the-human and Phil-the-scientist are one and the same, to a refreshingly strong degree.

Currently a Professor of Biomedical Engineering and the Stephenson Dean of the School of Data Science at UVA, Phil spent much of his career exploring and helping define the intersection of biomolecules and computation—as a practicing scientist and as a leader in academia, in open access academic publishing, in the broader open science movement, and in conjunction with industry and government for many years (e.g., as the Associate Vice Chancellor of Innovation and Industrial Alliances at UCSD).

How did you begin your career in bioinformatics?

Dr. Philip E. Bourne: Bioinformatics didn’t actually exist when I started my career.

…I started off with a Ph.D. in Chemistry, and then I drifted into an interest in biology.

I always had an interest in computing, so everything came together, particularly at the start of the Human Genome Project, in the 1990s; I was involved with the HGP when I was a postdoc at Colombia University, in New York. Part of the project was to collect large amounts of digital data. There was an absolute requirement to use computation to analyze that data. It became clear to me that this was the future.

Computing then started giving us results that allowed us to refine how we did our experiments; it was a virtuous cycle.

I ended up moving to the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC), because I was sure that this was the best place in the world to do this kind of work.

And, I guess, in many ways, I haven’t looked back. It’s been great.

What is your history with open access?

PB: This goes back to when I was the President of the International Society for Computational Biology, and then later, the Chair of the Publications Committee there.

At this time, I felt that bioinformatics, and more broadly, computational biology, was lacking journal-wise.

There were no journals that I really wanted to publish in. I wanted experimentalists to read what we were doing computationally.

I knew there was a real need for a new journal; I started talking to people at the Public Library of Science and I was enamored by what they were trying to do. Butdidn’t know much about open access and its value at the time.

From the very beginning, I was fully engaged with the journal. We recruited an Editor-in-Chief, and once we got started, I began to realize the full potential of open access. I really liked the idea that everything is free to read, even though there’s obviously a cost associated.

As a matter of fact, I wrote all sorts of articles about open access, and I also got involved with OA publishing communities.

I started to move on to other research projects, aside from the end publications; I became more concerned about the data and methods that we were using.

I remain a very firm supporter of open access. Funding agencies have really done a lot to push toward open scholarship. I think the level of open scholarship is currently only at the institutional level. The institutions are the place where I see a lot of activity now.

The lead author of a study is typically a student or a postdoc. Ultimately, the choice of where to publish is theirs. I encourage them to choose open access. If it’s not OA, then we always put a Preprint somewhere where people can read the final work.

What do you think is the future of open access?

PB: I’d like to ask the question, why don’t we have dynamic journals where, effectively, you can go and read the material, but at the same time, you can interact with that material?

So, instead of just looking at a graph, like a static graph in a paper, you could actually adjust parameters, and re-run all aspects of the experiment. This thus becomes a much more dynamic entity. This is possible now; most papers are not printed.

We’re still not using the full power of the environment.

What keeps you motivated?

PB: It’s all about where you feel that you can make a difference. For me, right now, that’s not writing papers.

Writing manuscripts is great for academic advancement. It’s useful, but it’s not necessarily pushing the needle as far as I would like to see.

Instead, what interests me is research output and doing something with it. Whether it be a product, or at least something that is tangible and useful. It could be a piece of software, or a high-quality dataset, for example.

To me now, these are as important as publications, if not more important. The system hasn’t caught up with that line of thinking.

You obviously have to do what’s best for your students, as they’re still being measured by traditional academic means, although this is clearly changing, to some degree. But it’s really about, I would say, the concept of usability.

Why did you decide to take the Big Data to Knowledge project on?

PB: I got to a certain point in my career where I had published plenty of papers and trained numerous students. I wanted to have an even bigger impact.

So, I approached the National Institute of Health (NIH). I was their First Chief Data Officer. As part of my role, I worked on the Big Data to Knowledge project.

Suddenly, we had this large influx of all sorts of data. How do we turn these into knowledge? I thought I could help to do that, not by doing it myself, but by supporting others to do that work.

We set up a whole series of projects. We set up different infrastructures to support big data research, and we got the NIH to accept Preprints as proof of work for grant applications, which actually, I think, is quite a big deal. It really helped propel Preprints.

How did you get the idea to set up the School of Data Science?

PB: I actually came to the University of Virginia not to set up a school, but to run the Data Science Institute.

However, the data science revolution was kicking off, and it presented a major opportunity. We were fortunate to receive the biggest gift in the university’s history.

The School is now an incredibly fast-growing enterprise with undergraduate and graduate programs. It’s a vibrant research environment, with 10 or 15 faculty members being added each year.

Students are really interested in data science. We have a minor class in data science right now, and students from 40 different disciplines are taking it. The key is to try and bring these disciplines together.

The problems we’re trying to solve are astronomical. It’s going to take teams of people working in an interdisciplinary way to address problems, in my opinion. Data science is a catalyst that can allow this to happen.

What do you like most about being a leader?

PB: The students. Seeing how excited they are by what they’re doing, and what they think they can accomplish. It doesn’t get any better than that.

What do you think the next frontier is for bioinformatics?

PB: I wrote an opinion piece about this, not that long ago in PloS Biology. It’s titled, ‘Is “bioinformatics” dead?’, and that was meant to be provocative. Of course, it’s not dead. The question is, thinking about what it was meant to be originally… is that the way it is today?

I think data science shows us that it’s really more about what I would call biomedical data sciences. It’s about taking what were once traditional bioinformatics data, which were of course genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, and combining that at multiple scales, all the way up to patient populations.

We need a complete multi-scale model, in which you can analyze large-scale population data, and figure out what’s going on at the molecular level, as it relates to, for example, particular disease states.

I think what’s interesting is that data science is something that encompasses so many different disciplines and fields, and we can learn from these.

For example, you can actually learn things from the application of data science to religious studies.

Some of these tools and processes add value in the frame of bioinformatics, that perhaps would not have been discovered without other fields. To me, this is a really exciting prospect.

Do you have any advice for new students in bioinformatics?

PB: Do it! Absolutely, do it. But think about the problems you’re trying to solve. Tackle the big problems, and do it with people who you really believe are already, or have the potential to make a difference.

Written by Cameron Mura, edited by Katherine Bosworth